by Louise Carleton-Gertsch

Recently, I asked some 14-year-old German students to think of a word that summed up what they thought about Shakespeare. The results were fairly predictable: boring, long, difficult, old, although a few did actually say creative. In fact, the majority of students today (even natives!) see Shakespeare as someone they have to read, rather than someone they want to. But there are a great many ways we can make Shakespeare and his plays come alive, and even fun, for teens!

Experiencing is key

It’s easy to forget that a lot of people in Shakespeare’s times were illiterate, so his plays were written to be performed and not read. And this is central to getting young people to engage with them today. Sitting behind desks and starting to read a play is almost certain not to engage them. But what will? Whether you decide to focus on the plot, explore a key scene, or look at certain character types, students should be encouraged to experience Shakespeare by acting things out. And the first step is to get them warmed up.

Warming up

Theatre-based warming-up activities are particularly good, but you need to create space for them. You could try the class activity “Go, stop, clap, jump”, which gets the students to listen and react fast.

Go, stop, clap, jump

Get the students to spread out. When you say “go”, they move around the room, exploring the space but keeping their distance from the others. When you say “stop”, they all stop and remain absolutely still until you say “go” again. The aim is to get the class to stop and go at the same time. Once the students have done this a few times and are paying attention, you can add other commands, e.g. “clap”, “jump”, “shout ’Who’s there?’”, “whisper ‘I am afraid’”. Mix up all of the commands to keep the students on their toes.

Or ask the class to show how certain types of character might move (“how does a king show he is a king?”). You could get students to create freeze frames in small groups that show characters in different situations (“show two people meeting in secret”, “show a messenger bringing the king important news”). Once the students have loosened up and are moving more freely you can then introduce a few stage directions with a line of text and get students to act them out in pairs, such as when King Duncan visits Macbeth (Act 1, Scene VI): A lady welcomes the king to her house. King Give me your hand. Take me to my host.

Note: When doing the above activities, it’s important to set time limits or keep them fast-paced so that students have to listen carefully and react quickly.

Getting to grips with the plot

It is important that students have an idea of what the play is about, even if you are only focusing on one scene. Instead of giving the students a summary to read, divide the plot into different parts and get small groups of students to create and then “perform” freeze frames in the right order. Alternatively, you could present the students with the opening of the play and the main characters and get them to predict what might happen (this obviously works best with plays that the students don’t know!).

Acting it out

When deciding which scenes to look at, start by choosing one that allows students to take charge and make choices. For instance, in the opening scene of Macbeth, students can think about what the witches look like, how they say their lines, how they enter, move and leave the stage, and whether they have any props or not. While it is not a key scene overall, it is short, not particularly difficult as far as language is concerned yet still introduces key themes. But before the students start tackling these questions, they should read the scene and address any language issues. Getting the class to do a choral reading of the text (or parts o it) helps them to avoid embarrassment about how to pronounce words and also enables you to direct the rhythm and pace. Which edition you use is entirely up to you, but don’t be afraid to use a simplified version of the text, or the graphic novel, so that students are given some support. And if you are doing a short scene, try to get the students to learn their lines by heart – this will enable them to speak more freely and give them a sense of achievement.

And at the end of the day, what could be more rewarding than hearing young people say “I know some Shakespeare” with a smile on their face?

Shakespeare Ausgaben für jede Altersstufe

7.-8. Klasse / A2: Short ‘n’ Simple

Romeo & Juliet

978-3-12-576194-0

Macbeth

978-3-12-576196-4

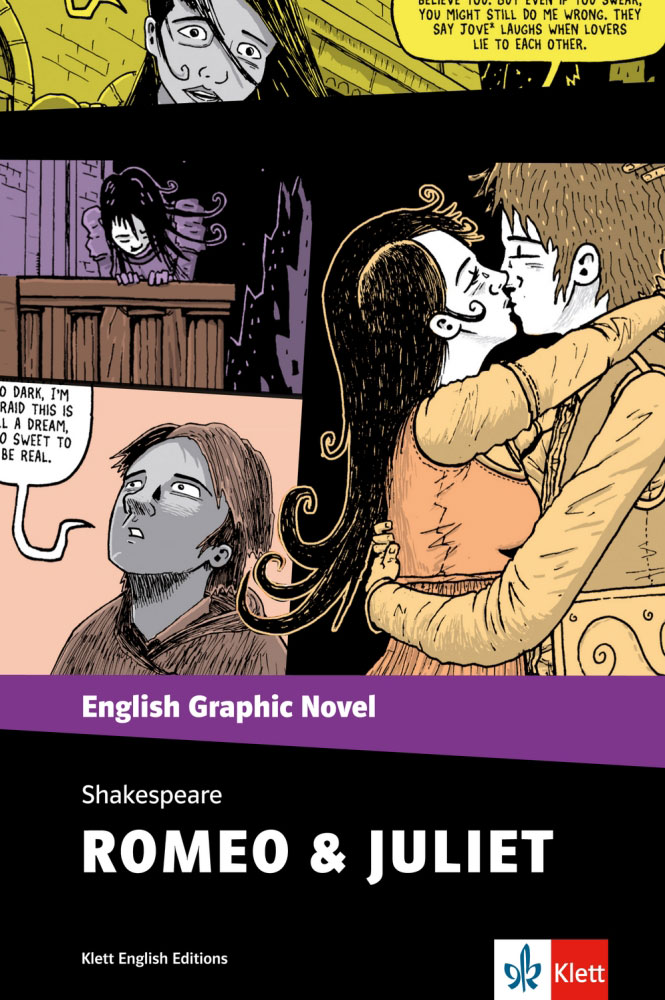

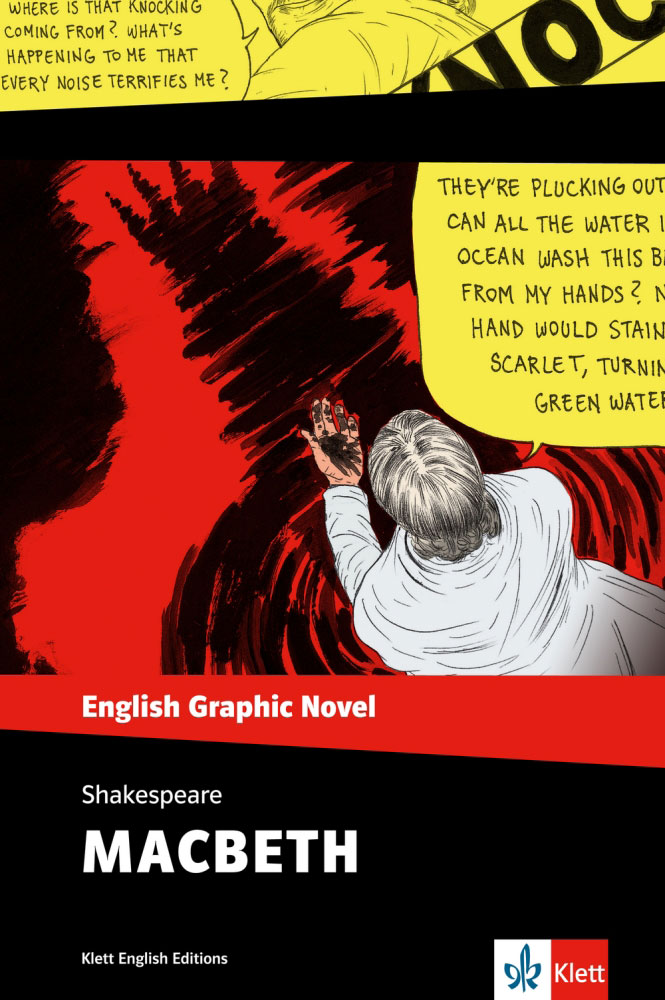

9–10. Klasse und für die Oberstufe: Graphic Novels – Shakespeares Ton in vereinfachter Sprache!

Romeo & Juliet

978-3-12-578216-7

Macbeth

978-3-12-578215-0

Das Original für die Oberstufe

Othello

978-3-12-576477-4

Romeo and Juliet

978-3-12-576473-6

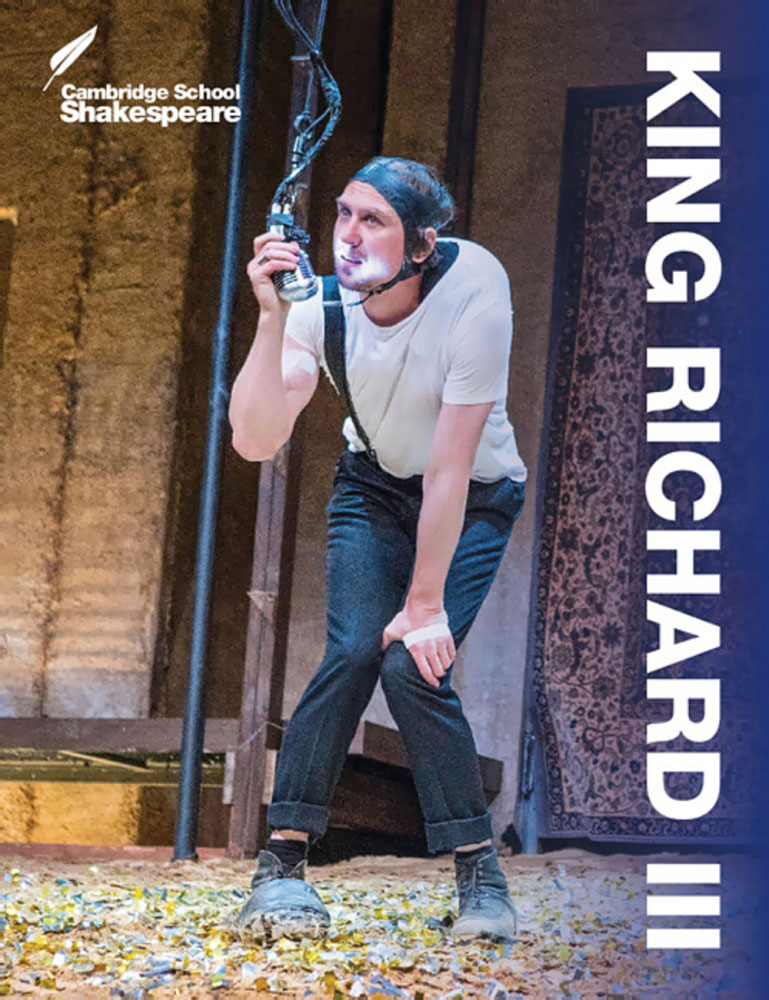

Richard III

978-3-12-576485-9